At the center of the small town of Chartres, a ninety-minute train ride away from Paris, sits a towering cathedral. This edifice, completed in the thirteenth century, has been the center of controversy because of a decision made in 2009 to renovate it. This is not the simple, patchwork maintenance performed on many old monuments; the cathedral’s once gloomy interior, blackened by centuries of use, is currently being painted a sunny, pale yellow. The paint job is part of a monumental attempt to restore the cathedral to its medieval appearance. But the renovation has inspired polemical responses.

The cathedral’s official website announces that the renovation will “bring about a radical change in our perspective of the place” [translation by author]. Yet, some are skeptical. Martin Filler, writer for the New York Review of Books, expressed his hope that “by some miracle this scandalous desecration of a cultural holy place can be reversed.” When I visited the cathedral three years ago, I stood in the middle of the scandal and the radical shift of perspective. I entered the cathedral, halfway through renovation and split by history. One half was the color of charcoal; the other half was full of color—bright whites and yellows gleamed in the intense light that shined through the newly cleaned stained glass windows. I was stunned by the contrast. At first, it may seem as though the renovation is destroying history; but those who take the time to appreciate the work that has been done come to realize that it is in fact uncovering history. An untrained eye can see very little in a cathedral obscured by centuries of dust, but using Chartres as a guide, modern visitors can learn to see cathedrals as their thirteenth-century counterparts saw them. Medieval visitors, looking at a myriad of colors accentuating stained glass, sculpture, and architectural detail, must have seen much more in a cathedral than we see today.

Northern rose window of Chartres cathedral. cc

Stained Glass

The purpose of stained glass is to tell stories and to invite light into a sacred space. As the years pass, the light is dimmed and the stories are silenced by dust. Modern tourists see only muted tones of colored glass, yet medieval visitors read the stories of the cathedral walls represented in vibrant color. During the renovation of Chartres Cathedral, the glass is being cleaned piece by piece, transforming the subdued glass back into lively stories and the shadowy cathedral into a place of light. Each time we visit a cathedral, we should imagine it full of light, and we should look for the stories that are being told in the glass.

Sculpture

The sculptures on the exterior of cathedrals have a story to tell as well, but these tales are often lost over time. Where medieval visitors saw beautiful representations of people, animals, and mythical creatures, modern visitors see only crumbling, often unrecognizable figures. At Chartres Cathedral you can see sculptures of the twelve apostles holding objects that symbolize how they were martyred. Yet time and wear erase details, effacing the life of the sculptures and the representations of apostles of old. Skilled masons at Chartres are renovating the sculptures to bring the figures back to life. In places where the sculptures haven’t been reanimated, we are left to our imaginations to envision what the sculpture once looked like.

Architectural Detail

In a cathedral that has not been renovated, the mélange of grey can blend together and hide the architectural details. Where paint has long since faded, visitors have the challenge of detecting the numerous architectural details in a sea of gray. Paint serves to accentuate the architecture of the building. At Chartres Cathedral, painters have chosen yellow and white paint to draw visitors’ attention to the vaulting in the ambulatory around the cathedral’s nave. If the renovation of Chartres Cathedral had been stopped at the point where I first saw it—half black, half yellow—it would have given visitors the unique opportunity to close one eye and imagine what today’s gloomy cathedral must have looked like centuries ago. Then, through the opposite eye, they would see if their imagination came close. This cathedral would have trained average travelers to discover the beauty of ancient architecture, as it did for me.

Unfortunately, the renovation will be completed next year; the old cathedral will be entirely masked by the new, and visitors will no longer have the rare privilege of witnessing the cathedral’s dramatic transformation in process. However, with this renovation complete, tourists can go to Chartres to see an example of what a medieval cathedral once looked like. And they can use that vision to help them uncover the beauty hidden in cathedrals that haven’t undergone such dramatic renovations. Next time you visit Notre Dame de Paris or Reims or any other cathedral, remember Chartres. Allow your imagination to peel back the layers of time and see cathedrals as they were meant to be seen. The answer will not be right in front of you, but maybe that is exactly what will intrigue you and push you to continue rediscovering cathedrals.

—Kayla Bowman

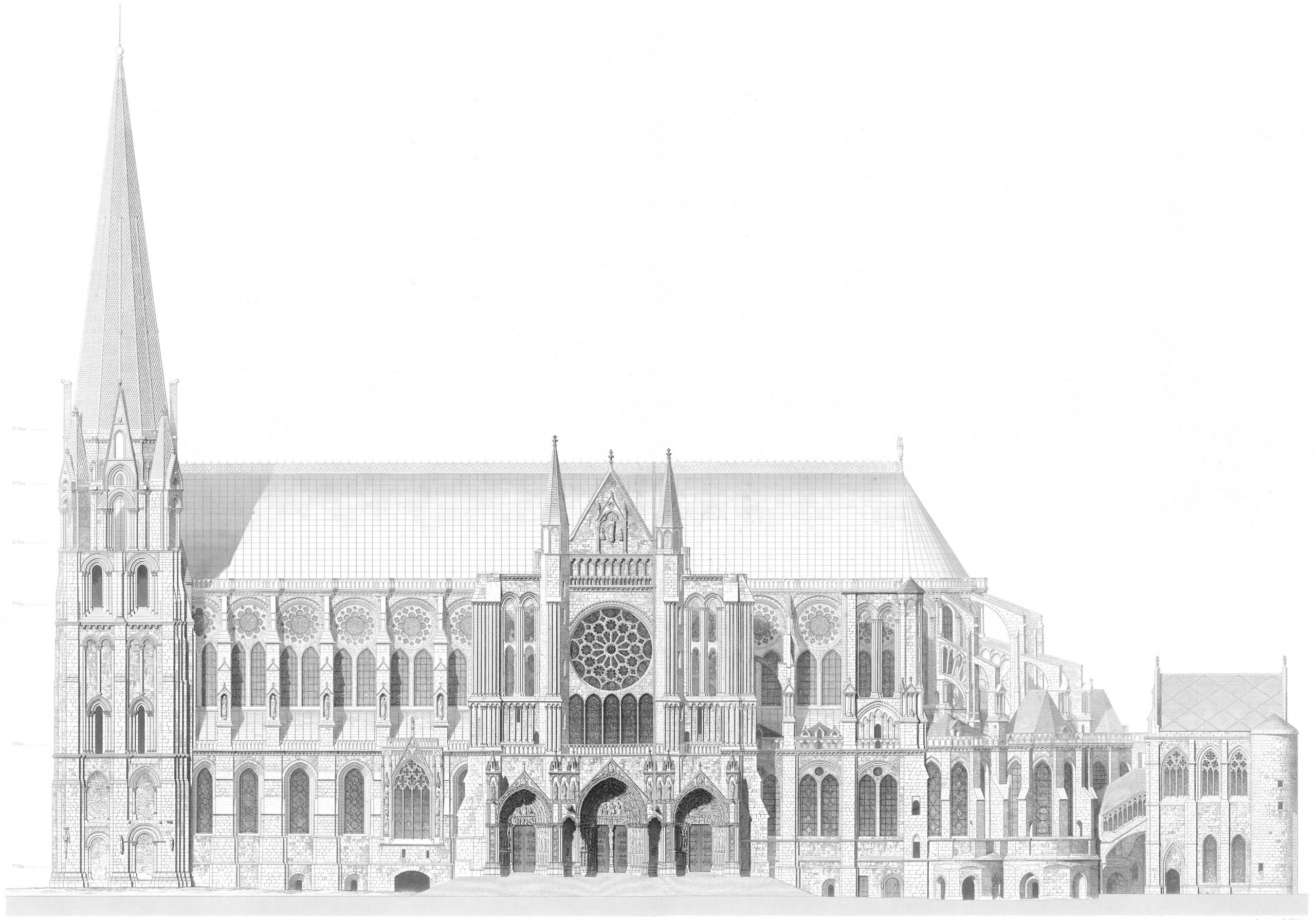

Featured image cc