North of Siem Reap in northern Cambodia and surrounded by encroaching jungles lies the world’s largest religious monument, Angkor Wat. The name Angkor Wat literally translates to City of Temples, indicating the temple’s massive size and grandeur.

Built in the early twelfth century, Angkor Wat is a luxurious and masterfully constructed temple spread across about 500 acres. Having been home to several faiths and cultures, now the temple is an icon of Cambodia, even appearing on the nation’s flag.

History

{{PD-US-expired}}

Angkor was the capital city of the Khmer Empire from the late ninth century until the empire’s fall in the fifteenth century. The Khmer controlled a large portion of Southeast Asia, including what is now southern China, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and parts of Vietnam.

While the Khmer were primarily an agricultural civilization, the many sites around Angkor, including Angkor Wat, illustrate that they were talented masons and artists. The beauty of many of their creations in and around Angkor have survived to this day.

Angkor Wat was commissioned by Suryavarman II, who ruled from 1113 to about 1150 AD. Construction on the temple ended shortly after the king’s death, leaving some of the art uncompleted. A few decades later, the city was ransacked by the Chams, a rival of the Khmer. As Angkor was repaired, the new king, Jayavarman VII, built new temples to the south of Angkor Wat.

Angkor Wat was originally dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu; however, by the end of the twelfth century, it had become a Buddhist temple, following the Khmer’s change of religion. Even today, Buddhist monks are the caretakers of the temple.

Photo by nalin a (cropped)

While Angkor fell to rising Thai powers in 1431, there is some disagreement as to whether Angkor Wat was ever fully abandoned. Some sources claim that remains of the Khmer people clung to the area and were even joined by Japanese Buddhists in the seventeenth century who mistook Angkor Wat for the famous Jetavana Buddhist monastery in India.

Other sources say that European explorers found Angkor Wat abandoned and in ruins, though no one believed the explorers’ claims of discovering a beautiful lost city out in the jungle. A Portuguese friar, Antonio da Madalena, explored Angkor in 1586 and gave a detailed account of the city, describing the building materials and architecture. However, he said he was unable to describe Angkor Wat satisfactorily because it was unlike any other monument that had ever been built.

Regardless of which accounts are accurate, the temple was largely unknown to Western civilization until Henry Mouhot, a French explorer, visited the area in the mid-nineteenth century. He returned home with reports comparing Angkor Wat to the Temple of Solomon and the ruins of Rome.

Mouhot’s reports so enchanted the French that in 1863, they claimed and invaded the area in order to take control of the ruins.

Several decades later, they set aside significant funding for the preservation and reconstruction of Angkor Wat and, though Cambodia became independent again in 1953, the French only paused their work in the 1970s and 1980s during the Cambodian Civil War and subsequent change of government.

Through the joint efforts of French and Cambodian restoration groups, preservation efforts have continued since the end of the mid-1980s, addressing centuries-worth of issues stemming from age, pillaging, water damage, and vandalism.

In 1992, the city of Angkor was named a UNESCO World Heritage site. Archeological efforts continue there even as the city welcomes 500,000 tourists each year, and Buddhists monks continue to maintain the temple as they have for centuries.

Art, Architecture, and Symbolism

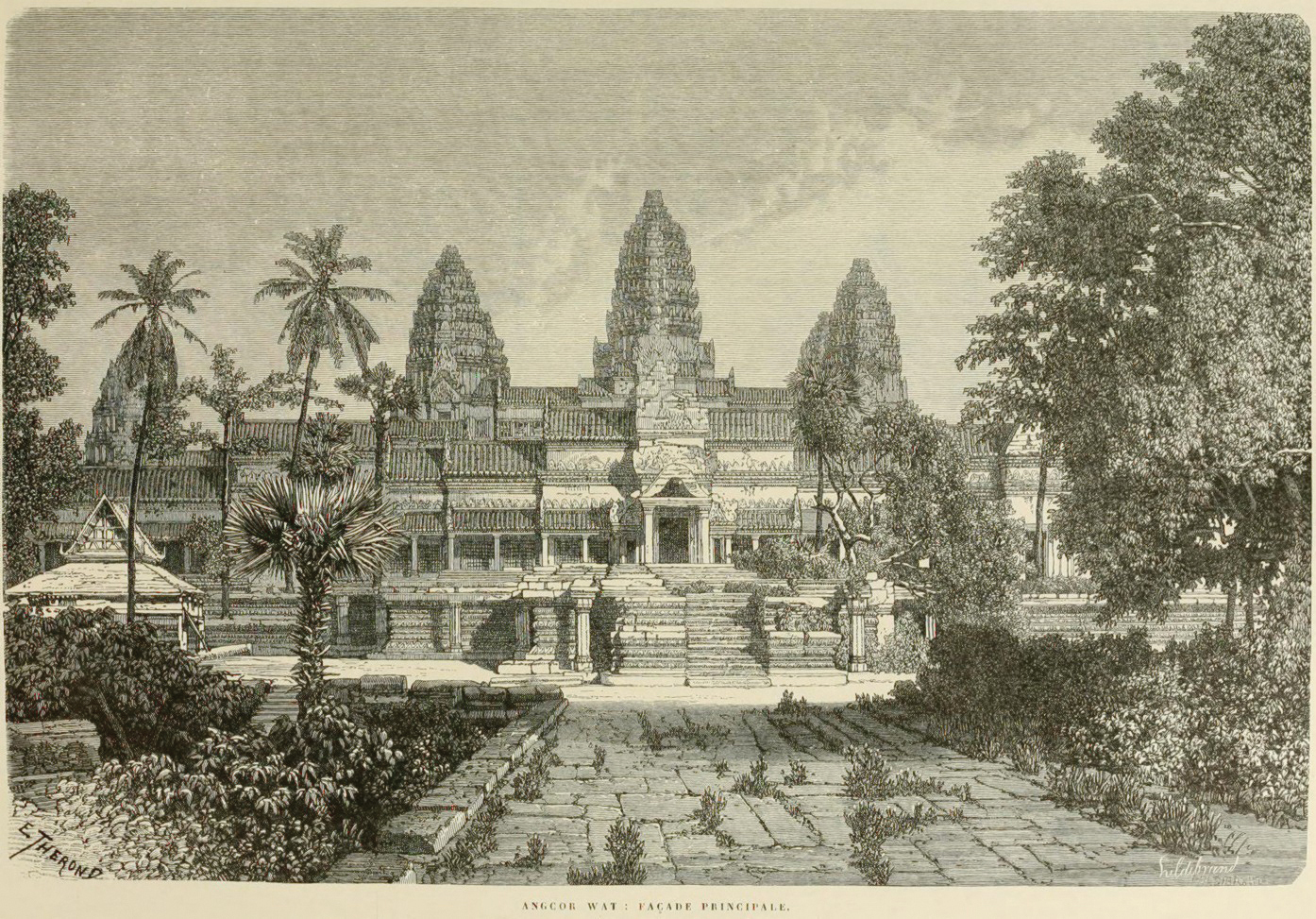

Angkor Wat is filled with symbolism from its very foundations. It is built in concentric rectangles, from the moat, to the wall, to three galleries raised above the city. Five towers rise from the innermost gallery with one tower at the center and the other four forming a square around it.

Angkor Wat is filled with symbolism from its very foundations. It is built in concentric rectangles, from the moat, to the wall, to three galleries raised above the city. Five towers rise from the innermost gallery with one tower at the center and the other four forming a square around it.

The five peaks of the temple are representations of Mount Meru, a mythical five-peaked mountain said to be the center of the physical, metaphysical, and spiritual universes in Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism. The wall surrounding the temple represents the mountain range that circles the world, and the moat outside the wall represents the ocean outside the world.

The walls of the temple are decorated in relief carvings. The art depicts events from Khmer history as well as myths and gods from Hindu tradition. Unlike in other Angkor temples, these are meant to be viewed from the right to the left. Often, they tell a story—a battle Suryavarman’s army fought, gods and demons churning the ocean of milk, several scenes from the Ramayana—that won’t make sense if viewed from the opposite direction.

Much of the restoration work done during the twentieth century was in reconstructing art that had been vandalized, though often the reconstructions were vandalized as well.

Angkor Wat stands out amongst Khmer temples for more than just its size and beauty. Most Khmer temples face the east (when you visit these temples, go in the early morning to appreciate the sunrise). Angkor Wat, though, was built facing the west. There is ongoing debate among archeologists and historians as to why Angkor Wat was built this way.

Some postulate that Angkor Wat was intended to be Suryavarman’s tomb or funeral temple. These scholars point to the art inside the temples as further proof of this theory because, like the temple’s orientation, it is backward. Traditionally, Khmer art was viewed in a clockwise pattern, but the art inside the temple is set up to be viewed counterclockwise. As funeral rites were also performed backwards compared to other rituals, the art and orientation seem to be absolute proof for the temple being a tomb.

Others, though, scorn this theory. They protest that the Khmer didn’t worship their kings as gods and that no temple would have been built to honor a king. Instead, they propose that the westward orientation refers to Vishnu, who was associated with that cardinal direction.

No matter the original reasoning for the unusual orientation, the temple doesn’t actually face true west. It is tilted just slightly to align with the sun on the spring equinox, and some of the art inside the temple is said to denote the seasons leading to and from the equinox as well.

The five towers are built with a series of tiers and topped with lotus flowers that come to a point. Even from a distance, the silhouettes invoke the image of the lotus, a symbol in Hindu culture that symbolizes the consciousness of the soul.

Angkor Wat’s delicate beauty has stood strong for nine hundred years and allows its visitors a rare peek into a talented and artistic culture. Steeped in religious symbolism, it brings its visitors closer to the Hindu religion it was originally built for while also introducing them to the saffron-robed Buddhist monks who care for the building and grounds. While not as well-known of a site as its western equivalents, Angkor Wat is a national treasure, and leaving it out of your list of monuments to visit would be a mistake.

—Bekah Luthi