It was my junior year, and school spirit drenched the sky on another cold night of football—I thought it was going to be a dull wait. But then the team came out, tearing off their helmets, their faces already glowing with sweat and their arms clenching. They lined up on the 30-yard line, facing the crowd in the stands. Then the team squatted with all knees and legs at the same angle.

They all struck at the same breath, palms and forearms coming together in a loud thwack. And then they screamed and roared with palms against thighs; other palms on chests—thwack—rocking to a beat as the leader screamed. They looked ready for war.

Everyone went ballistic.

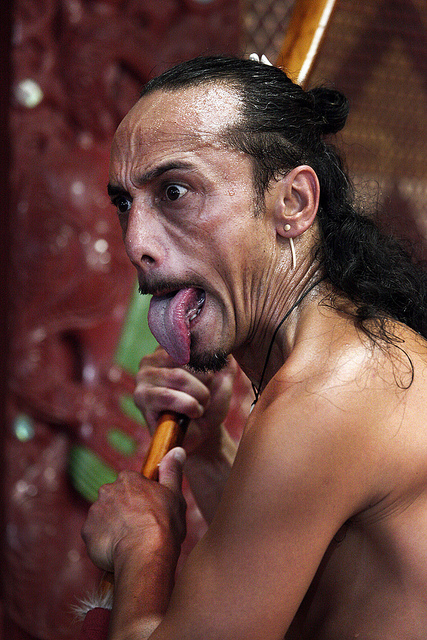

The first time you see it, the Haka looks like lines of huge, hulking men pounding on their arms and legs, yelling with tongues held out like lizards. That is the meaning of the Haka on the surface level: intimidation.

The Haka also symbolizes unity. In the words to the chant, the leader yells one syllable per beat:

Traditionally, performers stick out their long tongues to intimidate the enemy.cc

KA MATE! KA MATE!

It is death! It is death!

KA ORA! KA ORA!

It is life! It is life!

KA MATE! KA MATE!

We are all going to die!

KA ORA! KA ORA!

But now there is peace!

TENEI TE TANGATA,

PU-HURU-HURU

This is our leader, so hairy

NANA NEI I TIKI MIA,

Who fetched,

WHAKAWHITI TE RA!

made shine the sun of peace!

UPANE! KA UPANE!

Together! Keep together!

HUPANE! KAUPANE!

Up the step! A second step!

WHITI TE RA! HI!

Out comes the sun! Ahh

This chant can be scary but also beautiful. To some, the Haka inspires fear, but for others, it brings a connection to their ancestors and to their relatives. In a video on YouTube of a bride watching her relatives perform the Haka, the dance drove the bride to tears. For her, the Haka symbolized the death of one life but the birth of another life with her husband.

The Haka is part of a culture that is deeply rooted in New Zealand. According to Māori mythology, the Haka was a dance that symbolized the sun god Tama-nui-te-rā calling out to his wife, the Summer Maid, Hine-raumati. Together, they had a son, Tane-rore, whose name means “the trembling of air on a hot summer day.” This is why, in some versions of the Haka, the dancers quiver their hands.

Traditionally, the Haka was used to welcome a visitor, performed at weddings, or chanted before war. Now, the Haka has taken on a popular cultural twist, as you can see by my high school football team’s adaptation. Arguably, the most prominent Haka performance in popular culture was when the All Blacks New Zealand rugby team performed it at the World Cup 2011 before playing the French team. The video on YouTube has over 7.5 million views.

Since then, reports of the Haka have popped up everywhere, including a flash mob in London, a ceremony to mourn a fallen soldier in Afghanistan, a celebration of fifty years of peace between South Korea and New Zealand, and even a show before a Blood and Thunder Roller Derby World Cup.

Some have called these performances of the Haka an “inappropriate” use of the dance and a betrayal of its traditional roots. But others think differently, like Tom Maxwell, a soccer fan from London, who said, “It’s powerful. What I respect the most is the deep tradition of the Haka. Glad to see something can be continued such as this.”

Others still feel the bone-chilling reaction. Kane Campbell, a New Zealand native, commented, “As a New Zealander, every time I see the Haka it gives me goose bumps.”

Perhaps the most eloquent description of the Haka is from a comment on YouTube saying, there’s “a warrior spirit behind it.”

—Hannah Waller

Featured image courtesy of Kristina D.C. Hoeppner. cc